SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – A BUSINESS ECO-SYSTEM

In the 21st Century, we have emerged from process thinking into systems thinking. We have re-positioned global supply chains from linear operations focused on inventory optimization and cost-controlling process efficiencies, to re-think global supply chains as a complex system and using the analogy of the ecosystem to understand this complexity better.

Part 1 and Part 2 first.>

The Global SCL business eco-system is a complex system. To engage effectively in complex systems, we must enhance our systems thinking capabilities. Systems thinking is qualitatively and quantitatively different from process thinking. Process thinking is logically structured in a step by step modality from start to finish, from source to end user customer in a SCL context. Systems are multi-dimensional and multivalent, and involve many points of contact and modes of interaction.

The strategic leadership challenge is to develop a culture that takes us from robust supply chains, with an orientation to process efficiencies, to resilient supply chains, with an orientation to adapt effectively to multiple “normal” conditions and to instances of abnormality that require resilience in the face of crises, such as pandemics. Hence, there is the need to shift from process thinking

to systems thinking .

As a business eco-system, global supply chain logistics is both complex and fraught with multiple risks. Risk is inherent in that complexity, which itself is occasioned by the global extension of the system. Let’s look more closely at what is meant by “a business ecosystem” in order to understand better the inherent risks in complex global supply chain logistics.

The Global SCL business ecosystem is a network of organizations — including suppliers, distributors, customers, competitors, government agencies, and so on—involved in the delivery of products or services through both competition and cooperation .

Taking an organic approach, we recognize that each entity in the ecosystem affects and is affected by the others, creating a constantly evolving relationship in which each entity must be flexible and adaptable in order to survive and thrive. Flexibility and adaptability are the seeds planted in the Global SCL business ecosystem that need to be nurtured in a resilience strategy.

In an ecosystem, we encounter an entirely new dynamic that is integral to global business environments and international relations. These dynamics are not stratified in decision hierarchies, by which Peter Drucker characterized the post-war control and command models on which most corporations are built.

By contrast, a business ecosystem is an economic community

- supported by interacting organizations and individuals—the organisms of the business world

- that produces goods and services of value to customers, who are also members of the ecosystem

and involves member organisms:

- who have a stake in the success of the system as a whole

- who co-evolve their capabilities and roles within the system

- who align themselves with the directions set by one or more central companies

- which are valued by the community because it enables members to move toward shared visions, to align their investments and to find mutually supportive roles.

Again, the seeds of a resilience strategy are planted in a business ecosystem approach: stakeholders delivering and receiving value as contributors and participants, who apply and grow their capabilities individually as well as collectively, aligned to a common purpose and goal that constitute positive investments for the whole as well as for individual parts.

When an ecosystem thrives, it means that the participants have developed patterns of behavior that streamline the flow of ideas, talent, and capital throughout the system. It is to be noted that while product flow, and concomitantly competitive success, remain integral to the business side of a business ecosystem, great significance is also placed on ideas, talent and capital.

An eco-system is a culture and entails a strategic, not just a management, approach. The demand is for system-wide leadership, because you cannot manage an eco-system; you have to nurture it.

In a control and command culture, supply chain logistics is characterized as “hierarchical”, which most often refers to certain activities being outsourced to suppliers from which one buys and/or to intermediaries to which one sells. This is a linear and transactional model.

The steps include

- moving and transforming raw materials into finished products,

- transporting those products, and

- distributing them to the end-user.

The entities involved in the supply chain include producers, vendors, warehouses, transportation companies, distribution centers, and retailers. The corporate functions include product development, marketing, operations, distribution, finance, and customer service.

The goal is to lower costs and achieve faster production cycles. The core values are inventory optimization by managing:

- Velocity by reducing product storage times, increasing inventory turns, reducing transit times and border delays;

- Variability by eliminating unexpected changes in flow patterns and reducing the need for buffer inventories;

- Visibility by knowing where products are, when they will arrive, and levels of inventory in transit.

With this model, procurement, for example, focuses on managing contracts with suppliers to ensure quality at source. Supplier contract management, however, is distinctly different from supplier relationship management , where the emphasis is on managing the relationship, and not just the contract.

The dynamic is qualitatively and quantitatively different. SRM involves shared visions, the alignment of investments and mutually supportive roles among stakeholders. SRM is a supply chain logistics leadership qualification.

In effect, the traditional supply chain logistics process is an attempt to impose control and command over its operations. However, a well-run supply chain logistics process, no matter how international its reach, does not take into account variability, ambiguity, and uncertainty that is endemic to global competitive markets and international business contexts. Global supply chain logistics is too complex as a system to be controlled; there are too many players to try to command.

In the 21st Century, no matter how robust the efficiency of a supply chain logistics process is, it is generally not effective when doing business on a global scale. Even more significantly, that process is not capable of a sustained response to sudden and significant shifts such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The critical lesson to be learned from COVID-19 is that the new normal demands a new business paradigm and more strategic leadership capabilities.

That new business paradigm is to recognize global supply chain logistics as a complex system, to develop a deeper understanding of that complexity as a business eco-system and to position supply chain logistics leadership at the strategic level of organizational, economic, social, national, international, and environmental development.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – THE PURSUIT OF EXCELLENCE

If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.

- Wayne Dyer

In the 21st Century, we need

- to recognize global supply chain logistics as a complex system,

- to develop a deeper understanding of that complexity as a business eco-system and

- to position supply chain logistics leadership at the strategic level of organizational, economic, social, national, international, and environmental development.

Strategically, the Global SCL complex system benefits in three primary ways:

- Access to a broad range of capabilities, especially external capabilities that may be too expensive or time-consuming to build internally.

- Ability to scale quickly, because the modular or component structure, with clearly defined interfaces, makes it easy to add participants.

- Agility, because the modular setup, with a core direction but highly variable components, enable a degree of flexibility, a capacity to evolve, and a capability to be responsive.

In practical terms, what does it mean to call Global SCL a complex system? While the concept may hold merit, what proof is there to support the “complexity claim”?

Complexity is not synonymous with “difficult” and “challenging”. Anyone engaged in supply chain logistics manages challenging and often difficult processes in an effort to balance the “6-Vs”:

- Value for customers by controlling total landed cost while delivering quality and post-sales support

- Velocity reducing product storage times, increasing inventory turns, reducing transit time delays

- Variability eliminating unexpected changes in process flows and reducing buffer inventories

- Visibility regarding where products are, when they will arrive, and levels of inventory in transit

- Vulnerability of channel and product exposure to risk – natural and manmade, visible and invisible

- Verdancy /“Green Planning” focusing on environmental impact, carbon footprint, waste reduction

However, recognizing Global Supply Chain Logistics as a complex system requires a more strategic perspective. We need to change the way we look at things. We need to pursue excellence.

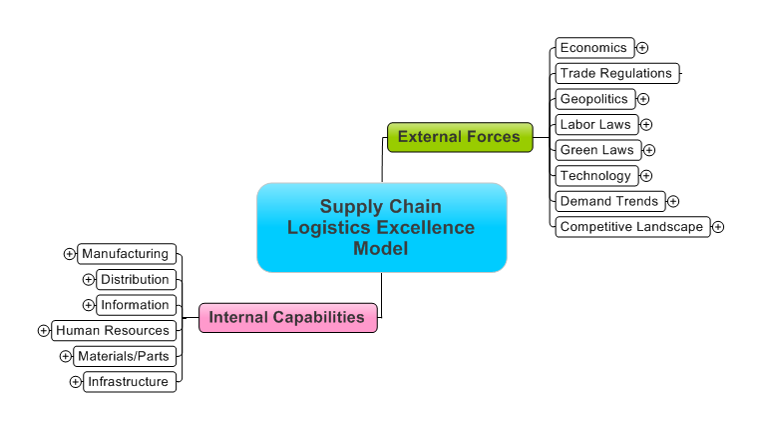

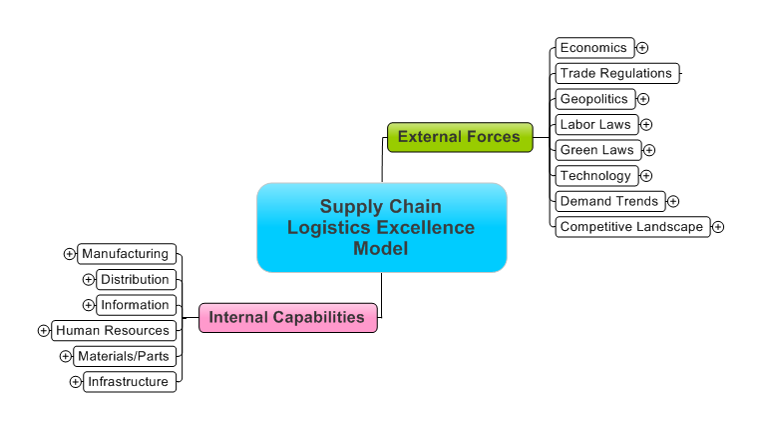

This Supply Chain Logistics Excellence Model incorporates research conducted by Singh and Cottrill, and published as Supply Chain 2020 Project Working Paper , and framed by the external forces and internal capabilities of competitive advantage.

In the pursuit of excellence on any level – corporate, economic, social and so on – Supply Chain Logistics must do more than balance the 6-Vs. As a complex system Global SCL involves:

This Supply Chain Logistics Excellence Model incorporates research conducted by Singh and Cottrill, and published as Supply Chain 2020 Project Working Paper , and framed by the external forces and internal capabilities of competitive advantage.

In the pursuit of excellence on any level – corporate, economic, social and so on – Supply Chain Logistics must do more than balance the 6-Vs. As a complex system Global SCL involves: By definition, a business ecosystem consists of independent economic players that agree to collaborate. Collaboration is a critical success factor. In the pursuit of SCL excellence, I identify two internal capabilities to illustrate the need to collaborate as a critical success factor.

By definition, a business ecosystem consists of independent economic players that agree to collaborate. Collaboration is a critical success factor. In the pursuit of SCL excellence, I identify two internal capabilities to illustrate the need to collaborate as a critical success factor.

ILLUSTRATION 1. DISTRIBUTED MANUFACTURING

Distributed manufacturing is a form of decentralized manufacturing practiced by enterprises using a network of geographically dispersed manufacturing facilities that are coordinated through information technology. Distributed manufacturing leverages large numbers of ‘partner’ factories and the talent of others to create agile supply chains.

This model dismisses location to find the best talent. The network allows for a specialist factory to fill excess capacity, while keeping manufacturing local to the product’s final destination, reducing emissions and logistics cost, and maintaining product quality. It is agile and scalable.

Whether implemented locally or internationally, distributed manufacturing requires leadership in negotiating and managing relationships with collaborating organizations.

ILLUSTRATION 2. FEDERATED SUPPLY CHAINS

The “federated business model” was first introduced by Peter Drucker in The Practice of Management , where he positioned organizations based on expertise, like orchestras or hospitals, in contrast to organizations structured in command-control hierarchies, like most companies.

Federation is based on the simple thesis that leaders cannot standardize or control the entire world, and must depend on others locally to lead as well as make contributions. The organizational model used by Drucker to illustrate this point is the orchestra conductor depending on the talent and expertise of the violinist or timpanist or any other member of the orchestra in the performance of a symphony.

On the one hand, collaboration requires a clearly defined organization , with clear roles and responsibilities , so that people speak to the same processes , with the same toolboxes . This ensures that all parties are “speaking the same language” and are using comparable plans.

On the other hand, differences should be highlighted . Leaders should be aware of the challenges and successes of regions, what they struggle with, and what they are proud of. Leaders should also be prepared to accept a different point of view on what is working locally and what is not, and be prepared to adapt the process to fit the right local requirement .

This kind of collaborative leadership requires interactive communication to ensure that when decisions are made, everyone is aware of it and is kept informed . It is the interaction that creates intelligence , in a cyclical view of new ideas, feedback, and response that drives new knowledge . Technology is the game changer that allows this to happen more quickly – but trust is the essential ingredient that allows data to cross boundaries, and forms the glue for federation.

The pursuit of excellence is highly interpersonal. Global SCL business eco-systems entail limited control of the overall system by each participant. Even an ecosystem orchestrator has limited means to enforce or control the behavior of partners, compared with a hierarchical supply chain model or an integrated business model.

The leadership challenge, therefore, is to engage and orchestrate external partners without full hierarchical power or control. However, a certain constraint on control is the price to pay for open innovation, flexibility, and resilience. Business ecosystem governance must be finely balanced, leaving room for serendipitous discoveries and self-organized evolution. Ultimately, it involves managing relationships between and among independent economic players.

The dynamism and flexibility of Global SCL ecosystems are opportunities and challenges: the complex system is evolvable and scalable, but it requires continuous adjustment, and therefore is not controllable. Sustainable success calls for permanent engagement with all stakeholders, improvement and expansion of the offering, and innovation and renewal of the ecosystem.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – COMPLEXITY AS RISK

Complexity demands leaders to think strategically. Strategic thinkers are contextual leaders who realize

- that there are no simple solutions;

- that there are many options and different strategies to be implemented, depending on the context;

- that whatever the plan, reality is unpredictable.

Contextual leaders have the capacity to exploit business moments and operational events in a way that enables them to make informed decisions and take effective action in varied, changing and uncertain situations. They are prepared for the “what if”. They are resilient.

Experiencing a “touch of overwhelm”, where do we begin? The clichéd answer is: Eat the elephant one bite at a time when dealing with an overwhelming task.

But think about it: what if that whole elephant was actually sitting in front of you? And what if you started eating it one bite at a time? It would go bad quickly. It would rot and stink up the neighborhood. And by consuming this elephant that way, you would get sick of it, since even the most delicious food will get tiring after a time.

Yet, the challenge remains in the face of complexity: How do we eat an elephant so that it doesn’t go bad and we don’t get sick of it? Hack it up and have a party. Cut it up into big parts and invite everyone to join in. In other words, collaborate, outsource, partner, distribute and “federate”. Go from serial analysis and decision making to parallel actions .

Step-by-step decision-making is a reductionist simplification of complexity. Complexity is multi-dimensional. SCL is an organic, holistic eco-system where each part is critically integral to all parts, and the whole is bigger than each of those parts. Given that SCL is complex, then a SCL resilience strategy must be dynamic in its ability handle ambiguity, uncertainty, and the complexities of each part and the whole at the same time.

We must plan and think collaboratively, recognizing that all parts demand both specific attention and relational attention: what do we need to do with respect to each issue? How do issues collide in such ways that our solutions need to account for the multiplicity of considerations?

Like a symphony orchestra, where players are grouped – strings , brass , woodwinds , percussion , in a business ecosystem, there are multiple environments in which businesses operate. Different from the orchestra sections, however, these business environments are external to the organization, yet simultaneously critical to the success of that organization and its operations.

Technically, we can define a business environment as: The sum total of all individuals, institutions and other forces that are outside the control of a business enterprise but the business still depends upon them as they affect the overall performance and sustainability of the business. Less technically but more cogently, an environment is everything we depend on.

There are two types of external environments that businesses operate in and interact with

External Micro Environments

- Suppliers who supply inputs such as raw materials and components

- Customers who buy and use a firm’s product and services

- Market Intermediaries who play an essential role in selling and distributing products to end user customers, and include distributors, wholesalers and retailers.

- Competitors who compete for sales with their products and for brand identity

- Publics who are groups that have an interest in a company’s ability to achieve its objectives, including environmentalists, media, interest and consumer protection groups

External Macro Environments

- Economic Environment includes (1) the type, nature, and structure of the economic system that exists in any region or country where the organization conducts business ; (2) the phase of the business cycle, such as the conditions of boom or recession; (3) fiscal, monetary and financial policies; (4) foreign trade and investment policies.

- Political and Legal Environment includes the political philosophy of the government in any region or country where the organization conducts business , recognizing that the public sector has a role in a country’s economic development, whereby the political framework implements regulations that influence the directions in which private business enterprises need to function.

- Technological Environment, beyond rapidly changing information technology, includes technology needed for the production of goods and services and consists of infrastructures, systems, machinery and processes available for use .

- Social and Cultural Environment includes the acceptance by both local people in regions where a company operates and populations worldwide (1) of activities in the conduct of the business, (2) of practices that do not violate cultural ethos of a society, (3) of social responsibility obligations to serve social interests and promote social well-being, and (4) socially responsive policies that relate operations and policies to the social environment in ways that are mutually beneficial to the company and society at large.

- Demographic Environment includes (1) the size and growth of population, (2) the life expectancy of people, (3) the rural-urban distribution of population, (4) the technological skills and educational levels of the labour force, where skills and ability of workers determine how well the organisation can achieve its mission; where the size of population and its rural-urban distribution determine the demand for the products; where the growth rate and age composition of the population determine the demand for goods.

- Natural Environment, beyond ecological and environmental concerns, includes the source of such inputs as raw materials, natural resources, minerals and oil reserves, water and forest resources, weather and climatic conditions, and energy.

Each environment is a dynamic force of influence on the other environments as well as on a business and its operations. These forces are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting myriad business opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – RISK FRAMEWORKS

An environment is a force of influence. It has an impact on how we operate within the constraints and opportunities, risks and capabilities constituting that particular environment.

There are two types of environments that have an impact on Global Supply Chain Logistics:

- External Micro Environments, which more closely affect the processes and operations of Supply Chain Logistics, including suppliers, customers, market intermediaries, competitors, and various publics.

- External Macro Environments, which more closely affect the global reach of Supply Chain Logistics, including economics, geo-politics, regulatory regimes, technology, culture, demographics, geography and natural conditions.

These forces are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting myriad business opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

There are several ways to approach risks in global supply chain logistics complex systems: Process and Value Stream Risks, Operational and Inherent Risks, and Risk Criticality.

VALUE STREAM: Focusing specifically on SCL process and value stream issues, we can identify

OPERATIONAL AND INHERENT: There are 4 “big buckets” in the Global Supply Chain Logistics complex system: Supply, Process, Demand and Environmental. Supply and Process are micro-environments; Demand and Environmental are macro-environments. Each entails operational risks and correlated inherent risks, as follows:

CRITICALITY: The most important approach to risk in Global Supply Chain Logistics focuses on criticality. By identifying critical levels, we can begin to develop mitigation plans.

The dynamism and flexibility of Global Supply Chain Logistics ecosystems present opportunities and challenges: the complex system is evolvable and scalable, but it requires continuous adjustment, and therefore is not controllable. Sustainable success calls for permanent engagement with all stakeholders, improvement and expansion, and innovation and renewal.

As with any business, and even any life situation, Global Supply Chain Logistics faces multiple forces of influence that are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting to myriad opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

Risks cannot be eliminated or even avoided. They are part of the tapestry in which businesses and societies operate. Resilience is about how we handle risk.

The dynamism and flexibility of Global Supply Chain Logistics ecosystems present opportunities and challenges: the complex system is evolvable and scalable, but it requires continuous adjustment, and therefore is not controllable. Sustainable success calls for permanent engagement with all stakeholders, improvement and expansion, and innovation and renewal.

As with any business, and even any life situation, Global Supply Chain Logistics faces multiple forces of influence that are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting to myriad opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

Risks cannot be eliminated or even avoided. They are part of the tapestry in which businesses and societies operate. Resilience is about how we handle risk.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – RISK MATURITY

Global Supply Chain Logistics is a complex system; we need to develop systems thinking, distinct from process thinking. Global Supply Chain Logistics is a business eco-system; we need to develop a more organic and holistic approach to how Global SCL works within multiple environments.

To move from robust to resilient Global Supply Chain Logistics, we need to look more closely at the nature and scope of Global Supply Chain Logistics:

- Global SCL is both a strategy and a process.

- Global SCL is about value creation, managing inter-organizational relationships, balancing multiple goals and agendas, and handling differences.

- Global SCL involves inventory optimization and network design.

- Global SCL demands holistic thinking and contextual leadership capabilities.

Organizationally, Global Supply Chain Logistics plays different roles and has multiple responsibilities:

- At the strategic level, it is responsible for delivering value, developing the business and competing successfully in global markets.

- At the organizational level, it is responsible for network and channel design, and managing inter-organizational relationships along those complex networks.

- At the process level, it is responsible for flow patterns, mitigating risks, managing landed costs, and delivering products in the marketplace.

- At the personal level, it is responsible for competitive leadership and professional competence, aka, sustaining a culture of trust.

The very nature and scope of Global SCL, how it is positioned within the organization, and how it operates all entail risk. The causes of risk are inherent in Global Supply Chain Logistics itself:

A Global SCL Risk Management Portfolio is less about risk avoidance and risk prevention, and more about risk acceptance and risk mitigation.

The effectiveness of any Risk Management Portfolio depends on the “risk maturity” of the organization generally and of Global SCL in particular. Enterprise Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization is to handle risk as a company:

A Global SCL Risk Management Portfolio is less about risk avoidance and risk prevention, and more about risk acceptance and risk mitigation.

The effectiveness of any Risk Management Portfolio depends on the “risk maturity” of the organization generally and of Global SCL in particular. Enterprise Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization is to handle risk as a company:

Global SCL Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization’s supply chain is to handle risk:

Global SCL Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization’s supply chain is to handle risk:

Establishing organizational excellence, seeing strength in risk and leveraging risk knowledge to competitive advantage are the foundation on which Global SCL strategy becomes flexible and agile.

Establishing organizational excellence, seeing strength in risk and leveraging risk knowledge to competitive advantage are the foundation on which Global SCL strategy becomes flexible and agile.

Interested in this topic? Check out these programs: Supply Chain Resilience, Supply Chain Strategies, Applied Innovation and more.

This Supply Chain Logistics Excellence Model incorporates research conducted by Singh and Cottrill, and published as Supply Chain 2020 Project Working Paper

This Supply Chain Logistics Excellence Model incorporates research conducted by Singh and Cottrill, and published as Supply Chain 2020 Project Working Paper  By definition, a business ecosystem consists of independent economic players that agree to collaborate. Collaboration is a critical success factor. In the pursuit of SCL excellence, I identify two internal capabilities to illustrate the need to collaborate as a critical success factor.

By definition, a business ecosystem consists of independent economic players that agree to collaborate. Collaboration is a critical success factor. In the pursuit of SCL excellence, I identify two internal capabilities to illustrate the need to collaborate as a critical success factor.

The dynamism and flexibility of Global Supply Chain Logistics ecosystems present opportunities and challenges: the complex system is evolvable and scalable, but it requires continuous adjustment, and therefore is not controllable. Sustainable success calls for permanent engagement with all stakeholders, improvement and expansion, and innovation and renewal.

As with any business, and even any life situation, Global Supply Chain Logistics faces multiple forces of influence that are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting to myriad opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

Risks cannot be eliminated or even avoided. They are part of the tapestry in which businesses and societies operate. Resilience is about how we handle risk.

The dynamism and flexibility of Global Supply Chain Logistics ecosystems present opportunities and challenges: the complex system is evolvable and scalable, but it requires continuous adjustment, and therefore is not controllable. Sustainable success calls for permanent engagement with all stakeholders, improvement and expansion, and innovation and renewal.

As with any business, and even any life situation, Global Supply Chain Logistics faces multiple forces of influence that are constantly in action and changing, engaging and connecting to myriad opportunities in a complex and multifaceted interplay of issues, causes, and effects. As a result, they manifest foreseeable, as well as unpredictable and unprecedented, risks.

Risks cannot be eliminated or even avoided. They are part of the tapestry in which businesses and societies operate. Resilience is about how we handle risk.

A Global SCL Risk Management Portfolio is less about risk avoidance and risk prevention, and more about risk acceptance and risk mitigation.

The effectiveness of any Risk Management Portfolio depends on the “risk maturity” of the organization generally and of Global SCL in particular. Enterprise Risk Maturity

A Global SCL Risk Management Portfolio is less about risk avoidance and risk prevention, and more about risk acceptance and risk mitigation.

The effectiveness of any Risk Management Portfolio depends on the “risk maturity” of the organization generally and of Global SCL in particular. Enterprise Risk Maturity  Global SCL Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization’s supply chain is to handle risk:

Global SCL Risk Maturity depends on how prepared an organization’s supply chain is to handle risk:

Establishing organizational excellence, seeing strength in risk and leveraging risk knowledge to competitive advantage are the foundation on which Global SCL strategy becomes flexible and agile.

Establishing organizational excellence, seeing strength in risk and leveraging risk knowledge to competitive advantage are the foundation on which Global SCL strategy becomes flexible and agile.