SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – FLEXIBILITY

Establishing organizational excellence, seeing strength in risk and leveraging risk knowledge to competitive advantage are the foundation on which Global SCL strategy becomes flexible and agile. Flexible supply chains are able to adapt quickly to changes and risk events while maintaining customer service levels. There are two key points specific to Global SCL: adaptability and customer service.

Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 first.>

In other words, we are not just referring to adaptability aimed at organizational survival; we are specifically focusing on the customer service context. The value proposition of flexible Global SCL is customer satisfaction, not just operational integrity or process efficiencies. Flexible Global SCL strategically sustains organizational excellence and competitive advantage by being customer engaged, that is, by focusing on people as the end user and beneficiaries of the SCL service.

Flexibility is complex. It has a range of meanings from the ability to be easily modified to the willingness to change or compromise. Ability entails an impact/response; willingness entails a decision/action. Even more significantly, flexibility is a trait or attribute that describes the extent to which a person, organization, or society can cope with changes in circumstances and think about problems and tasks in novel, creative ways. In effect flexibility is personal, organizational and cultural.

There is no such thing as one kind or one approach to flexibility, especially in the Global SCL context. Minimally, we must consider various types of flexibility, their application to supply chain logistics and the tactics needed to handle them. A selection follows:

- Capacity Flexibility involves longer term arrangements with suppliers that feature reserved capacity not immediately committed to production, allowing scalability when demand increases, including when risk events occur, with shorter lead times and assurance of supply.

- Physical Flexibility involves work units that can be reconfigured and repurposed to produce different products on demand, along with the capacity to expand operations and facilities.

- Design Flexibility involves the ability to redesign and test parts and product inputs to adjust to multiple market requirements including customer demand and environmental impact.

- Product Flexibility involves interchangeability and repurposing of parts and product configurations to support inter-operability strategies and reduce inventory redundancies and obsolescence.

- Lead-Time Flexibility involves product replenishment and quick-time delivery strategies in response to demand shifts, customer preferences and the need to mitigate risk events.

- Supply Chain Design Flexibility involves multiple responsive supply chains dedicated to different needs , including such examples as build-to-order, build-to-plan, build-to-stock, and build-to-spec supply chains.

- Logistics Flexibility involves the ability to adjust the route taken to move goods, funds or information between points, by providing choices for inventory deployment and modes of transport selection.

- Material Flexibility involves the ability to re-engineer products and product content in the face of resource shortages and risk demands.

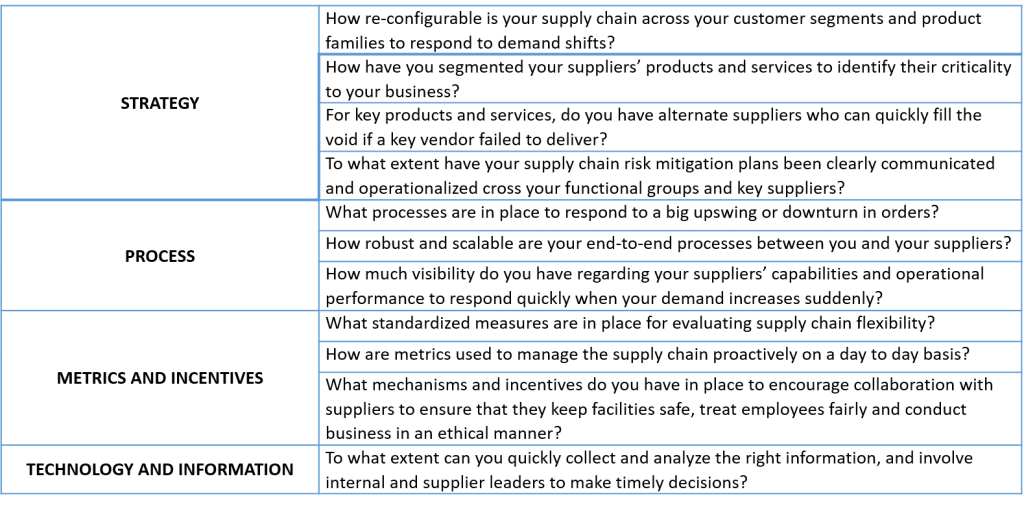

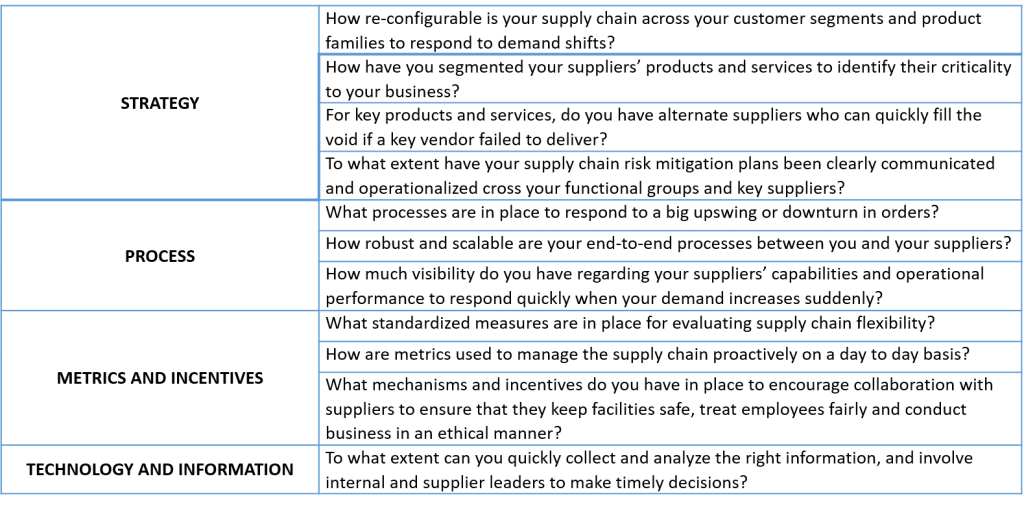

To create flexible Global SCL, it is necessary to integrate strategy, processes, metrics and technology across the business and among suppliers. A holistic approach involves questions that must be asked of internal stakeholders as well as key suppliers

.

Global SCL flexibility must be system-wide in assessing the capabilities and flexibility of key suppliers, and ensuring that these strategic partners are in sound financial health. We can call that “flexibility at source”.

Moreover, Global SCL flexibility must be assimilated into the business culture so that at a strategic level, the company can respond to demand shifts, build collaborative relationships with suppliers, and collect and analyze data for timely and accurate decisions. We can call that: “flexibility as strategy”, ”flexibility as process”, and “flexibility as operations”.

Flexible and responsive Global SCL enables companies to effectively work with suppliers and efficiently serve customers, no matter the market conditions or the risk events. Flexibility provides choices, and choices directly support greater Global SCL resiliency.

Global SCL flexibility must be system-wide in assessing the capabilities and flexibility of key suppliers, and ensuring that these strategic partners are in sound financial health. We can call that “flexibility at source”.

Moreover, Global SCL flexibility must be assimilated into the business culture so that at a strategic level, the company can respond to demand shifts, build collaborative relationships with suppliers, and collect and analyze data for timely and accurate decisions. We can call that: “flexibility as strategy”, ”flexibility as process”, and “flexibility as operations”.

Flexible and responsive Global SCL enables companies to effectively work with suppliers and efficiently serve customers, no matter the market conditions or the risk events. Flexibility provides choices, and choices directly support greater Global SCL resiliency.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – AGILITY

In the face of uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk, leaders need to lead with an agile mindset. That immediately begs two questions: what is agility? And what is an agile mindset?

Where flexibility is an organizing principle, agility denotes action: the ability to move quickly and easily and the ability to think and understand quickly. In business we can apply such agile characteristics to organizations and people as changing direction quickly while keeping balance, strength, speed and control. Although speed and power are important, the main movements are turning, moving, pivoting.

Agile is not a playbook. It is not a set of directions. It is not a checklist. Agile assumes that the end users’ needs are ever changing in a dynamic business world, and the organization’s response can meet and exceed expectations. In the face of crisis and pandemics, however, ordinary change becomes extraordinary, and the speed to respond is more critical. The agile leader can turn, move, and pivot, with the power to maintain strength and exercise control in a timely way.

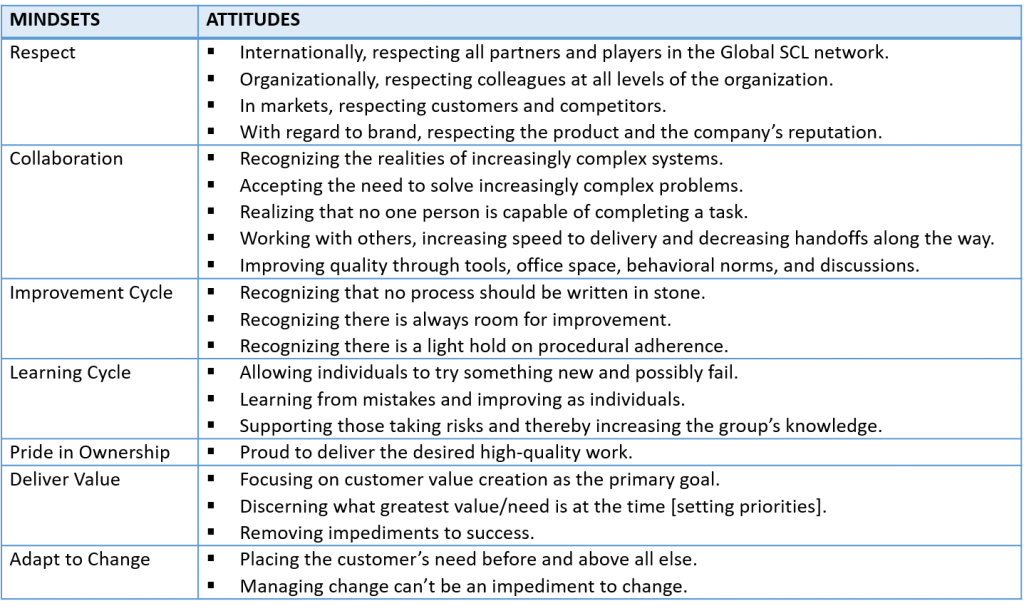

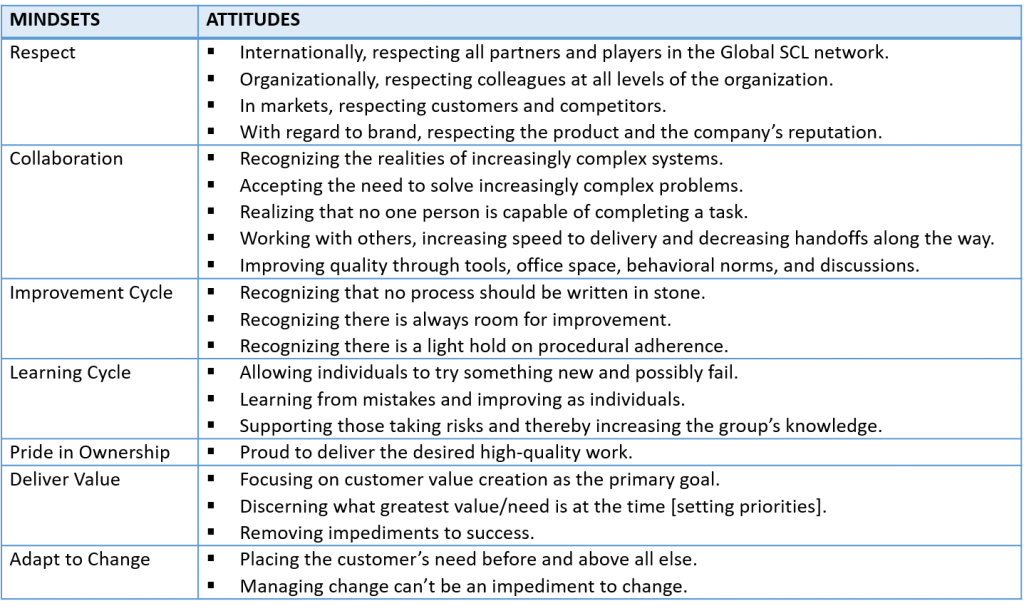

Agility is more than a leadership attribute and trait. It is a mindset and a culture – and it needs buy-in across an entire organization in order to succeed: An agile mindset is the set of attitudes supporting an agile environment. These include respect, collaboration, improvement and learning cycles, pride in ownership, focus on delivering value, and the ability to adapt to change. This mindset is necessary to cultivate high-performing teams, who in turn deliver value for customers, organizations, societies, and the global community.

The qualities and attitudes of an agile mind are

To sharpen our understanding of the Agile Mindset as a cultural phenomenon, we contrast it to the more traditional bureaucratic mindset:

To sharpen our understanding of the Agile Mindset as a cultural phenomenon, we contrast it to the more traditional bureaucratic mindset:

To develop an agile mindset and culture, organizations need to cultivate the following:

To develop an agile mindset and culture, organizations need to cultivate the following:

- Conscious Culture Change: shift the focus from activities and tasks to outcomes and results. Policies, protocols and processes are subject to scrutiny, discovery, innovation and experimentation in the pursuit of better performance.

- Employee Engagement: dynamic, progressive and demonstrated employee engagement is the engine of the agile process. Where the right tools and technologies are important, people ultimately govern whether business agile is superficial or substantial.

- Results-Driven Collaboration: internal and external collaboration must be effective, efficient, in-context and result-based. It can’t be blocked by silos, bottlenecked by politics, and suffocated by an excess of communication where the volume of discussion becomes more notable than the quality and relevance.

- Speed with Efficiency: working faster isn’t the point. Speed must be combined with efficiency so that people spend less time on administrative tasks, and more time moving tasks to completion.

- Agile Resource Management: reliable, real-time information is needed to make on-the-fly adjustments to work-at-hand. Spreadsheets and emails are out, and drilling down into schedules, skillsets, assignments and availability is in.

- Visibility: agility is about being nimble, flexible and response-ready by ensuring that decisions and actions align with overall strategic priorities and direction. This only happens when decision-makers have 360-degree visibility, and can monitor situations, identify trends and make proactive decisions.

- Collaborative Work Management: put the right Collaborative Work Management (CWM) tools and technologies in place to support employees, enable performance and drive results.

The Agile mindset is an attribute of practitioners more than theorists. It is pragmatic and action-oriented more than a theoretical philosophy. It goes beyond a set of beliefs and becomes a tool for diagnosis and the basis for action. It tends to be built on the hard-won knowledge of experience and crafted from the lessons of trying to cope with massive change in the face of incomprehensible complexity.

Steve Denning, Understanding the Agile Mindset, Forbes

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – DYNAMIC DECISIONS

In the Art of Resilience , we identified two critical practices worthy of consideration when handling risk and risk events in complex systems like Global SCL:

- Don’t need all the answers. When we try hard to find the answers in the face of traumatic events, that trying too hard can block answers from arising. There is strength in knowing that it's okay not to have it all figured out right now and trusting that we will gradually know when we are ready.

- Menu of capabilities. We need to have lists of possible actions, plans and processes that support our strategies and alternative directions when we need them most.

Both practices speak to a dynamic approach to decision making: answers arising naturally as a form of discovery, and our capability to discern possibilities and potential solutions are core to being resilient.

Impediments to resilience are built into how we conduct business internationally and how we organize Global SCL in terms of command-and-control and process management. As noted in blog #8,

- Global SCL is too comfortable with deterministic models and tools, such as forecasting models, sales and operations planning, and other processes that never take uncertainty into account.

- Global SCL processes are driven by cost management and delivery improvements, which are not comprehensive enough to handle complexity, and cannot effectively deal with risk and risk events.

The brutal fact is that Global SCL growth results in uncertainty, complexity and risk growing in frequency and severity. There is a need to utilize probabilistic tools to account for these factors. Before we can identify which probabilistic tools to use, we need to understand more fully the similarities and differences among different ways we make decisions. In organizations, various types of decisions apply:

From this taxonomy, we can build a culture around dynamic decision making. We start with the question: What is Dynamic Decision Making?

Dynamic decision-making is interdependent decision-making that takes place in an environment, aka a complex system, which changes over time either due to previous decisions which have an impact on that environment or due to events that are outside of the control of the decision maker. Dynamic decisions, unlike conventional one-time decisions, are more complex and occur in real-time. They involve the extent to which people intuitively use their experience to handle complex systems.

Dynamic decisions are complex in themselves. They

From this taxonomy, we can build a culture around dynamic decision making. We start with the question: What is Dynamic Decision Making?

Dynamic decision-making is interdependent decision-making that takes place in an environment, aka a complex system, which changes over time either due to previous decisions which have an impact on that environment or due to events that are outside of the control of the decision maker. Dynamic decisions, unlike conventional one-time decisions, are more complex and occur in real-time. They involve the extent to which people intuitively use their experience to handle complex systems.

Dynamic decisions are complex in themselves. They

- Involve a series of decisions to reach a goal, not a single decision;

- Include the interdependence on previous decisions, which are not isolated from previous decisions;

- Work in changing environments, not in static fixed environments that do not change;

- Entail real time pressures , not situations with no time pressures.

Dynamic decision environments have the following characteristics:

- Dynamics: refers to the dependence of the system's immediate state on its previous state, driven by positive feedback or negative feedback, respective examples of which are the accrual of interest in a savings bank account or the elimination of hunger by eating .

- Complexity: refers to the number of interconnected elements in a system that make it difficult to predict the behavior of the system as a whole and also of its individual parts in terms of the number of components in the system, the number of relationships between them, and the nature of those relationships. Complexity is also a function of the decision maker's ability to handle complexity.

- Opaqueness: refers to the physical invisibility of some aspects of a dynamic system and also depends on a decision maker's ability to acquire knowledge of the components of the system .

- Dynamic complexity: refers to the decision maker's ability or inability to control the system using the feedback the decision maker receives from the system, caused by the complexity of the system itself and can include:

o Opaqueness causing unintended side-effects.

o Dynamic, non-linear relationships between components.

o Feedback delays between actions taken and their outcomes.

Dynamic decision making does not focus on what you decide; nor does it frame a process on how you reach a decision. It is not a deterministic model and does not include a step by step checklist.

Dynamic decision making is probabilistic. It focuses on and identifies probable solutions that are themselves not complete and final. Probable solutions may lead to possible actions, which themselves are situational and contextual – applicable for the moment so long as they contribute value.

Dynamic decision making is situational and aligned to an agile mindset. As a tool in probabilistic modeling, it focuses on risk-informed decisions and the value of managerial flexibility. In effect, dynamic decision making is a way to gain insight into potential uncertainties, their probability, their impact and interdependencies, weighing the value of options that introduce greater flexibility into the organization.

Dynamic decision making supports the ability of strategic leaders to lead in context.

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – NON-RATIONAL DECISIONS

Complexity demands leaders to think strategically. Strategic thinkers are contextual leaders who realize

- that there are no simple solutions;

- that there are many options and different strategies to be implemented, depending on the context;

- that whatever the plan, reality is unpredictable.

Contextual leaders have the capacity to exploit business and operational events in a way that enables them to make informed decisions and take effective action in varied, changing and uncertain situations. They are prepared for the “what if”. They have agile mindsets. They are dynamic decision makers. They are resilient.

Organizations and systems that evaluate performance based on the ability to navigate complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity will ultimately prove to be most effective in handling risk and dealing with risk events. They value contextual intelligence.

Contextual intelligence is the ability to quickly and intuitively recognize and diagnose the dynamic contextual variables inherent in an event or circumstance and results in intentional adjustment of behavior in order to exert appropriate influence in that context. This is easier said than done.

Our minds automatically try to place data in a framework that allows us to make sense of our observations and use them to understand events and predict them. Contextual intelligence, however, confronts the reality of randomness.

Randomness works against our pattern-finding instincts. It tells us that sometimes there is no pattern to be found. As a result, randomness is a fundamental limit to our ability to plan and control. It acknowledges that there are situations and processes that we can't predict, such as pandemics. It is stochastic, lacking any predictable order. It brings us to the fringe where planning is no longer effective.

Yet, at the fringe we discover possibility that opens the door to innovation. In the face of complexity, as well as associated risk and risk events, we need to make risk-informed decisions and to value flexibility. We need dynamic decision making capabilities to gain insight into uncertainties, their probability, their impact and interdependencies, allowing us to weigh the value of options that introduce greater flexibility into the organization. That is innovation in the handling of the unexpected.

To understand contextual intelligence more fully, let’s consider the difference between a “plan” and a “strategy”. “Strategic Planning is an oxymoron.” Ann Latham, What The Heck Is A Strategy Anyway? Forbes, October 29, 2017

A strategy is a framework for making decisions about how you will play the game of business. These decisions, which occur daily throughout the organization, include everything from capital investments to operational priorities to marketing to hiring to sales approaches to branding efforts to how each individual shuffles his/her To Do list every single morning.

A plan, by contrast, is a process that involves study, analysis, design, execution, evaluation, and adjustment. Anyone in management is familiar with such planning models as

Rational Decision Making is the most universally accepted decision model, to the point where it is often called the Traditional Decision Making process. Despite variations, it usually involves 7 steps:

Rational Decision Making is the most universally accepted decision model, to the point where it is often called the Traditional Decision Making process. Despite variations, it usually involves 7 steps:

- Define the problem.

- Identify decision criteria.

- Allocate measures to the various criteria.

- Develop alternatives to consider.

- Evaluate the alternatives .

- Select the best (or highest ranked) alternative.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the decision.

There are two major weaknesses with Rational Decision Making:

- Bounded Rationality: Decision-making is limited by the information available, the decision-maker’s cognitive limitations, and the finite amount of time available to make a decision.

- Satisficer: Leads to a “satisfactory decision”, not necessarily to the best, most appropriate or most effective decision, that is, the acceptable but not the optimal option.

More significantly, the Rational Decision Making model does not work well in the face of ambiguity, uncertainty, complexity and risk. Physiologically, it engages only the left rational brain; it fails to engage the right creative brain. Stress, which is related to fear, and risk, which is related to ambiguity in complex systems, ignite the intuitive right brain. As a result, decision making needs to be more creative, dynamic, and agile minded.

Planning benefits directly from Rational Decision Making. By contrast, strategy benefits from Non-Rational Decision Making.

Non-Rational or Dynamic Decision Making is the pursuit of optimal, not just acceptable, decisions, by “maximizers”, not satisficers, who use heuristic methods to make decisions in the face of uncertainty about whether the choices will lead to benefit or harm. The decision is a “value analysis” not the selection of the best alternative.

Non-Rational Decision Making is heuristics-driven, that is, it focuses on maximizing performance across all variables and makes value trade-offs that include a reduction strategy to eliminate variables and an accommodation strategy to include variables.

Non-Rational Decision Making uses experience-based techniques for problem solving, instead of a structured approach. Emotion is a factor in the decision-making. It demonstrates a tolerance for risk, and leads to decisions under conditions of deep uncertainty. Adaptive decision strategies are designed to evolve in response to new information. It holds multiple views of the future as “possibilities” and “opportunities”, and uses ranges of plausible probability to describe deep uncertainty.

Non-Rational Decision Making embraces robustness rather than optionality to assess alternatives. Where Traditional Rational Decision-making ranks alternative options contingent on best estimate and decides that there is a best (i.e., highest ranked) option, Non-Rational Decision Making uses robust approaches to describe tradeoffs. Tradeoffs include

- trading a small amount of optimum performance for less sensitivity to broken assumptions,

- trading one good performance for multiple alternatives over a wide range of plausible scenarios,

- keeping options open, which is the basis of a “resilience strategies” handling “what if” scenarios.

Ultimately Non-Rational Decision Making reverses the order of traditional decision analysis by conducting an iterative process based on vulnerability-and-response-option analysis rather than on a predict-then-act decision framework.

Non-Rational Decision Making characterizes uncertainty in the context of a decision. It identifies those combinations of uncertainties most important to the choice among alternative options and describes the set of beliefs about the uncertain state of the world that is consistent with choosing one option over another. This allows stakeholders to understand the key assumptions underlying alternative options before committing themselves to those assumptions.

Strategic Leadership = Contextual Intelligence + Agile Mindedness + Non-Rational Decision Making

SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS – APRES INTRODUCTION

The Logistics Institute uses the collective identifier “Global Supply Chain Logistics”, shortened as Global SCL, to express 21st Century socio-economic and business realities and to position Global SCL as a leadership strategy for companies, business sectors, society collectively and people individually. As a value chain, Global SCL is a complex system.

As a complex system, Global SCL faces risk at many levels – inherent and operational, in its external micro and external macro environments. Global SCL is risky business. Handling risk is its métier.

In effect, Global SCL is a microcosm of the realities we face as societies and individuals. Insights into the dynamics of Global SCL provide a framework, if not a roadmap, on how we can meet the leadership challenges of being flexible and agile in the face of ambiguity, uncertainty, and the unknown.

With COVID-19, Global SCL is recognized as an essential service. More than that, however, at the root of COVID-19 is complexity, which we face every day as confusion and information overload. Global SCL is a model on how to understand complexity and handle its dynamics in order to develop an agile and flexible culture prepared to handle the unexpected.

Global SCL is not a solution to solve the COVID-19 problem, precisely because COVID-19 is not just a problem. It is a dilemma. A dilemma involves circumstances in which choices must be made between two or more alternatives that seem equally undesirable , whereas problems are difficulties that have to be resolved or dealt with .

COVID-19 is itself a complex dilemma of global magnitude. No solutions will work until we embrace the dynamics of complexity and can handle the risks endemic to complex systems. The world in which we live is a complex system, and COVID-19, along with global financial crises and the collapse of the international banking system, among others, is an integral part of that world and how it works, not just an untimely aberration.

What is applicable in the competitive business context of complex Global SCL is applicable in a social context when handling risk. It is the need to be resilient. We end this series on RISK TO RESILIENCE: A LEADERSHIP STRATEGY at the beginning: what is Global Supply Chain Logistics?

In the 21st Century, Supply Chains and their co-relative Integrated Logistics, aka strategically called “Supply Chain Logistics”, are key to competitive success in global business markets. To understand this reality, we must first understand what it means to be competitive.

There are three determinants of competitive success:

Value, that is, what is the real value companies deliver in the global market?

Market, that is, who are your customers and what do they want?

Competition, that is, how well do you understand your competition and their success factors?

Competition is no longer product vs product, but supply chain vs supply chain. In the pursuit of Supply Chain Logistics excellence, we must look more closely at the external forces and internal capabilities of competitive advantage.

Furthermore, linear supply chains have morphed into global value webs. Supply Chain Logistics is best understood as a business eco-system. As such, Supply Chain Logistics is a business enabler, a revenue driver, and a competitive differentiator.

As market dynamics shift from traditional systems to global markets, and further to ecommerce, we must consider both direct and indirect market channels. The impact of this shift on Supply Chain Logistics is disruption and dis-intermediation.

The challenge is for Supply Chain Logistics professionals and practitioners to rethink everything. With the emerging “brave new world” of Big Data, this is even more critical. Value is based on knowledge exchange along complex highly interconnected global webs. The shift is immediate and far reaching: from transactions as the primary business goal to creating knowledge-sharing networks as the primary business goal. The challenge is to develop contextual intelligence shared across Supply Chain Logistics Ecosystems.

Contextual Intelligence is a strategic decision model, and competitive advantage is the ability to navigate complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity. In the 21st Century, Supply Chain Logistics Ecosystems demand contextually intelligent leaders.

More traditional approaches separate Supply Chains and Logistics and position them in a service economy, with a specific emphasis on organizational structures , process flows from suppliers to customers , and tactical operations [buy, transport, warehouse , replenish .

Supply Chains and Logistics, however, are no longer just back room operations. Modern Supply Chains and Logistics are no longer simply linear processes; they are complex networks, aka SCL Ecosystems. Even more significantly, SCL Ecosystems are sources of the company’s competitive advantage: the principal business drivers, embracing all the mission-critical activities needed to drive business growth, increase market share and generate revenue and profits.

To position the SCL Ecosystem as the company’s competitive advantage, we begin by redefining the traditional business model from the point of view of the market: BUSINESS STRATEGY: In the market, companies deliver value, not just products or services.

SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY: Supporting value are the inter-organizational networks of global suppliers upstream and of international customers/ consumers downstream .

LOGISTICS STRATEGY: Supporting these inter-organizational value webs are integrated end-to-end logistics processes: procurement, asset management , and distribution management .

ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY: Supporting this entire value-web are the enablers: IT, policies and procedures , facilities and equipment , and most notably organizational structures.

Reporting mechanisms and organizational hierarchies are cornerstones of success, as is technology, but they are not the primary focus of competitive advantage in a market-drive business model.

With Global SCL we need to rethink corporate structure and competitive advantage in the face of complexity. Competitive advantage is not command and control; it is being agile and flexible in the face of ambiguity, uncertainty, and the unknown.

BUSINESS STRATEGY: In the market, companies deliver value, not just products or services.

SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY: Supporting value are the inter-organizational networks of global suppliers upstream and of international customers/ consumers downstream .

LOGISTICS STRATEGY: Supporting these inter-organizational value webs are integrated end-to-end logistics processes: procurement, asset management , and distribution management .

ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY: Supporting this entire value-web are the enablers: IT, policies and procedures , facilities and equipment , and most notably organizational structures.

Reporting mechanisms and organizational hierarchies are cornerstones of success, as is technology, but they are not the primary focus of competitive advantage in a market-drive business model.

With Global SCL we need to rethink corporate structure and competitive advantage in the face of complexity. Competitive advantage is not command and control; it is being agile and flexible in the face of ambiguity, uncertainty, and the unknown.

Interested in this topic? Check out these programs:

Global SCL flexibility must be system-wide in assessing the capabilities and flexibility of key suppliers, and ensuring that these strategic partners are in sound financial health. We can call that “flexibility at source”.

Moreover, Global SCL flexibility must be assimilated into the business culture so that at a strategic level, the company can respond to demand shifts, build collaborative relationships with suppliers, and collect and analyze data for timely and accurate decisions. We can call that: “flexibility as strategy”, ”flexibility as process”, and “flexibility as operations”.

Flexible and responsive Global SCL enables companies to effectively work with suppliers and efficiently serve customers, no matter the market conditions or the risk events. Flexibility provides choices, and choices directly support greater Global SCL resiliency.

Global SCL flexibility must be system-wide in assessing the capabilities and flexibility of key suppliers, and ensuring that these strategic partners are in sound financial health. We can call that “flexibility at source”.

Moreover, Global SCL flexibility must be assimilated into the business culture so that at a strategic level, the company can respond to demand shifts, build collaborative relationships with suppliers, and collect and analyze data for timely and accurate decisions. We can call that: “flexibility as strategy”, ”flexibility as process”, and “flexibility as operations”.

Flexible and responsive Global SCL enables companies to effectively work with suppliers and efficiently serve customers, no matter the market conditions or the risk events. Flexibility provides choices, and choices directly support greater Global SCL resiliency.

To sharpen our understanding of the Agile Mindset as a cultural phenomenon, we contrast it to the more traditional bureaucratic mindset:

To sharpen our understanding of the Agile Mindset as a cultural phenomenon, we contrast it to the more traditional bureaucratic mindset:

To develop an agile mindset and culture, organizations need to cultivate the following:

To develop an agile mindset and culture, organizations need to cultivate the following:

From this taxonomy, we can build a culture around dynamic decision making. We start with the question: What is Dynamic Decision Making?

Dynamic decision-making is interdependent decision-making that takes place in an environment, aka a complex system, which changes over time either due to previous decisions which have an impact on that environment or due to events that are outside of the control of the decision maker. Dynamic decisions, unlike conventional one-time decisions, are more complex and occur in real-time. They involve the extent to which people intuitively use their experience to handle complex systems.

Dynamic decisions are complex in themselves. They

From this taxonomy, we can build a culture around dynamic decision making. We start with the question: What is Dynamic Decision Making?

Dynamic decision-making is interdependent decision-making that takes place in an environment, aka a complex system, which changes over time either due to previous decisions which have an impact on that environment or due to events that are outside of the control of the decision maker. Dynamic decisions, unlike conventional one-time decisions, are more complex and occur in real-time. They involve the extent to which people intuitively use their experience to handle complex systems.

Dynamic decisions are complex in themselves. They

Rational Decision Making is the most universally accepted decision model, to the point where it is often called the Traditional Decision Making process. Despite variations, it usually involves 7 steps:

Rational Decision Making is the most universally accepted decision model, to the point where it is often called the Traditional Decision Making process. Despite variations, it usually involves 7 steps:

BUSINESS STRATEGY: In the market, companies deliver value, not just products or services.

SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY: Supporting value are the inter-organizational networks of global suppliers upstream

BUSINESS STRATEGY: In the market, companies deliver value, not just products or services.

SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY: Supporting value are the inter-organizational networks of global suppliers upstream